#9 - Unraveling the Skeletal Melodic Line

FOR Advanced Students

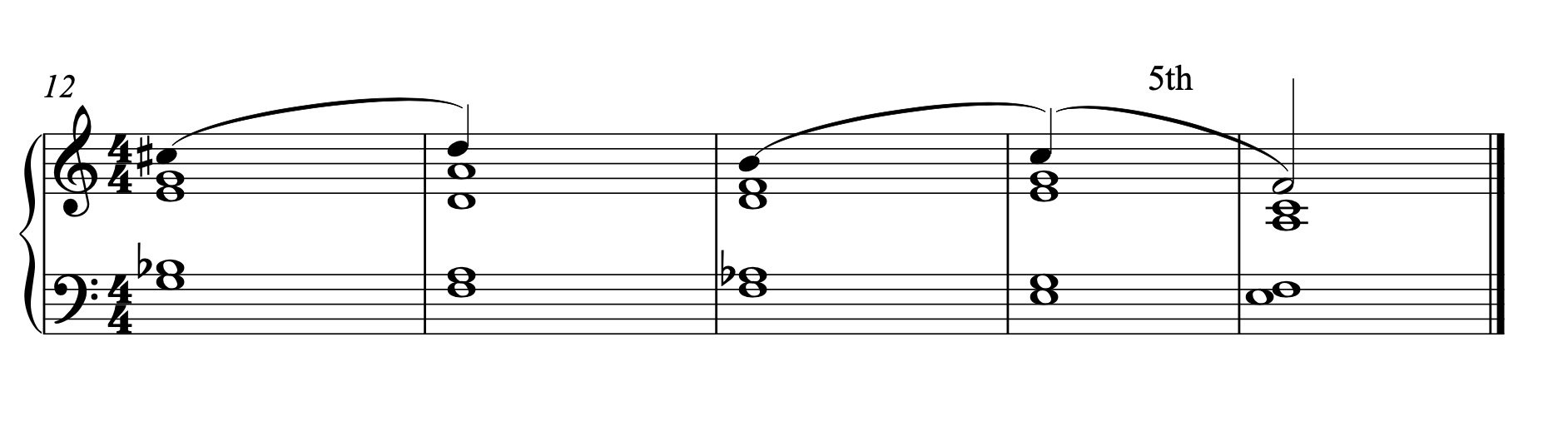

Unlike the excerpt analyzed in the previous blog post of J.S. Bach’s Prelude in C Major (BWV 846), which contained four measures, the following excerpt that we will analyze in this blog post is fifteen measures long! This shows that prolongation can, and does often occur over longer stretches - in fact, depending on the depth of the layer of analysis, much longer. In a later blog post I will show how these first nineteen measures create one unit of meaning, but for this blog post we will focus on these fifteen measures alone (m. 5-19), and only for the treble clef for an abundance of clarity.

Schenkerian Analysis – a big scary term that holds within it what I consider to be the most profound and beautiful art form – is a phenomenal way of unraveling the essence of a composition by determining the hierarchy between the sea of notes, since we know that they are not all equal to one another (specifically, the first, third and fifth scale degrees are stronger than the others due to their emergence in the harmonic series, and therefore form the harmonic backbone of most pieces of music up until the mid-19th century).

And so, Schenkerian Analysis posits that there are two main types of melodic lines: a 5-line (a melody that starts from the 5th scale degree of the key), and a 3-line (a melody that starts from the 3rd scale degree of the key). The two tasks that are before us today are: A) determining which one is used in this piece, and B) examining how this skeletal melodic line is being prolonged.

Without further ado, let’s look into the content of these fifteen measures, and answer the two questions posed above, one at a time.

New York: G. Schirmer, 1893. Plate 11015

LESSON 1

Determining The Line

1) If we go back to measure 1 of this piece, we are reminded that the soprano note is E, which is the 3rd scale degree in the key of C Major (they key of this prelude). Furthermore, upon analyzing the first four measures, we saw that they are in essence a prolongation of that very same E. This already suggests a 3-line, but we’d have to examine this further to determine if that is indeed the case.

2) A 3-line would go down from the third scale degree, through the second, to the first. And so, we need to find the other two scale degrees in order to conclude that this is indeed a 3-line. We find these two pitches in measures 6 (D) and 8 (C). I will justify this determination in the next how section.

3) Notice the B in measure 11, which, in the larger scheme of things functions as a lower neighbor to the tonic, but in this case supports a very different localized progression. I will get back to this at a later segment in this post.

LESSON 2

The 5th Motif, The Engine

1) It is time to address the elephant in the room – what’s up with all these jumps of fifths? We are taught in counterpoint to shy away from big jumps, and this excerpt is rife with them: measures 5-6, 7-8, 9-10, 15-16 and 17-18. In preliminary theory, as well as ear training, we learn of the pull of the fifth (the dominant) toward the first (the tonic). In more advanced theory, we learn about how this pull could be harnessed to localize every note and harmony – so in essence, the idea that every note has its own dominant (a.k.a. secondary dominants). So, how is it used here?

2) I suggested the importance of the D in measure 6, claiming it was a structural 2 within the 3-line. This could be now justified by seeing how the A in measure 5 is a fifth away from the D in measure 6. In other words, the A leads to the D, therefore prolonging it.

3) The same thing is happening in the next two measures, as the G in measure 7 is a fifth away from the C in measure 8. In other words, the G leads to the C, therefore prolonging it. We can therefore conclude that this is an important motif that is being used to propel the music forward.

4) This concludes the initial 3-line: E (m. 1), D (m. 6), C (m. 8). It is an rather initial line, since once we will go further out in resolution, we will see this is “just” a localization of the 3-line.

Lesson 3

Masterful Prolongation

1) Upon looking at measures 12-15, it would be easy to conclude that there is another highlighting of D (m. 13) and C (m. 15) by using lower neighbors. While this is true, it is only so on the surface. The actual architecture is far more beautiful! But before we unravel the beauty of measures 12-15, let’s try to get a clearer idea of the bigger picture.

2) Notice the motif of the 5th between measures 15-16 (C to F). If we follow the previous premise of the 5th resolving to a note of importance, this means that F is a note of importance, and is being prolonged by C. But F is the fourth scale degree in C Major, and I contended that the melodic line employed is a 3-line. What is its function, then? Clearly, the F is an upper neighbor to the E in measure 19.

3) Behold the gorgeousness of Schenkerian Analysis! So, we established that F (m. 16) serves as the upper neighbor to E (m. 19), and that C (m. 15) leads to F (m. 16) by using the 5th motif. If we look closely into measures 12-15, we can see two layers of prolongation in it: D (m. 13) serves as an upper neighbor to C (m. 15), which in turn leads to F (m. 16), the upper neighbor of E (m. 19); but, beautifully, C# (m. 12) serves as the lower neighbor to D (m. 13), and B (m. 14) serves as the lower neighbor to C (m. 15). In addition, the B in measure 11 serves as a larger lower neighbor to the C in measure 15.

4) What this really means is that the C in this case (m. 15), normally a tonic, is actually the 5th of F (m.16), and that B (m. 11) is the lower neighbor to that 5th! In other words, that very same note, C, now has a completely different function.

5) Are you able to see the two layers of prolongation? The more immediate one of the lower neighbors in measures 12 and 14 to prolong the C in measure 15, and the deeper layer of E (m. 19) being the structural note of importance, which is being prolonged by its upper neighbor F (m. 16), that is approached by the 5th motif using C (m. 15). Isn’t that marvelous?!

6) Finally, notice measure 1, and compare it to measure 19. Do you see how it is exactly the same figure, only a full octave below? And so, hopefully now it is becoming clear how music prolongation works, and how precious its understanding is to us as performers.

Advanced Practice

A complete diagram of the ideas discussed in this post could be summarized as such:

There are a few ideas here that weren’t discussed in this post, but they are also very telling.

1) Notice that m. 19 resolves at an Imperfect Authentic Cadence (a tonic cadence with the soprano not being the 1st scale degree). Beyond the idea of completing a full octave descent, this is done in order to signal that our journey is not over yet! It will be over once we reach a Perfect Authentic Cadence (a tonic cadence with the tonic at the soprano as well), which will be of importance at the continuation of this analysis. Up until then, the tension and suspense is mounting!

2) We discussed the importance of the 5th as a motif in this piece, and a common practice in Schenkerian Analysis is to highlight the inverse of such motifs - in this case, the 4th. These fourths, present in the bass clef on measures 10-11 (D to G) and 18-19 (G to C), lead each in turn to a cadence: measures 10-11 to a Half Cadence, and measures 18-19 to an Imperfect Authentic Cadence.

3) Finally, notice the intervals between the notes on measures 5, 7, 13 and 15: fourths and fifths!

A Final Thought

All of these measures, 1-19, have one goal in mind – to prolong E in the soprano! Harmonically, the goal is prolong the tonic - and not just to prolong the tonic, but rather exactly the same voicing the was used at the beginning. Astonishing, isn’t it? What a wonderful rollercoaster that brings us back to our point of departure, albeit being rattled by the experience, only to continue onto the next stretch of the ride.

Also, notice the gradual increase of the unit of importance from the segment we covered in the previous blog post (m. 1-4 - four measures long), to this one (m. 5-19 - fifteen measures long). This increase is integral to the architecture of this piece, as it plants seeds as ideas, that grow and blossom magnificently until they become a beautiful and vibrant tree. And we are only halfway there! This importance will be more apparent as we continue to analyze this piece, and take a farther and farther look from the individual notes into the birds-eye vantage point, which will reveal the true essence of this piece.